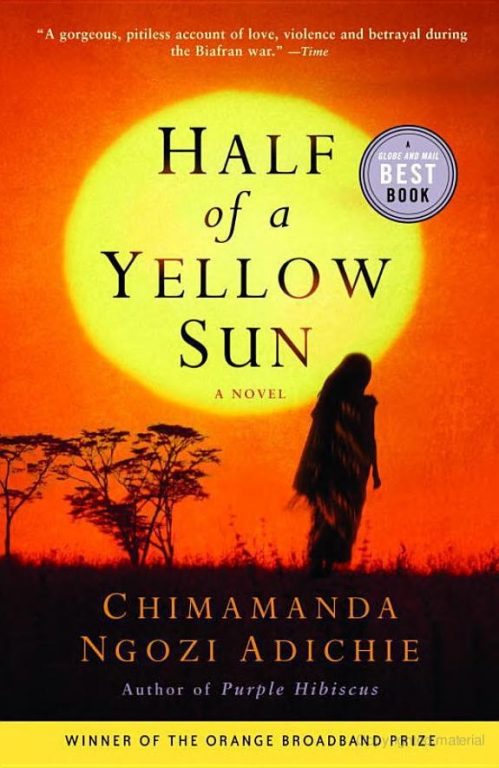

Half of a Yellow Sun

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

From Publishers Weekly

Starred Review. When the Igbo people of eastern Nigeria seceded in 1967 to form the independent nation of Biafra, a bloody, crippling three-year civil war followed. That period in African history is captured with haunting intimacy in this artful page-turner from Nigerian novelist Adichie (Purple Hibiscus). Adichie tells her profoundly gripping story primarily through the eyes and lives of Ugwu, a 13-year-old peasant houseboy who survives conscription into the raggedy Biafran army, and twin sisters Olanna and Kainene, who are from a wealthy and well-connected family. Tumultuous politics power the plot, and several sections are harrowing, particularly passages depicting the savage butchering of Olanna and Kainene’s relatives. But this dramatic, intelligent epic has its lush and sultry side as well: rebellious Olanna is the mistress of Odenigbo, a university professor brimming with anticolonial zeal; business-minded Kainene takes as her lover fair-haired, blue-eyed Richard, a British expatriate come to Nigeria to write a book about Igbo-Ukwu art—and whose relationship with Kainene nearly ruptures when he spends one drunken night with Olanna. This is a transcendent novel of many descriptive triumphs, most notably its depiction of the impact of war’s brutalities on peasants and intellectuals alike. It’s a searing history lesson in fictional form, intensely evocative and immensely absorbing. (Sept. 15)

Copyright Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

From The New Yorker

Based loosely on political events in nineteen-sixties Nigeria, this novel focusses on two wealthy Igbo sisters, Olanna and Kainene, who drift apart as the newly independent nation struggles to remain unified. Olanna falls for an imperious academic whose political convictions mask his personal weaknesses; meanwhile, Kainene becomes involved with a shy, studious British expat. After a series of massacres targeting the Igbo people, the carefully genteel world of the two couples disintegrates. Adichie indicts the outside world for its indifference and probes the arrogance and ignorance that perpetuated the conflict. Yet this is no polemic. The characters and landscape are vividly painted, and details are often used to heartbreaking effect: soldiers, waiting to be armed, clutch sticks carved into the shape of rifles; an Igbo mother, in flight from a massacre, carries her daughter’s severed head, the hair lovingly braided.

Copyright 2006 Click here to subscribe to The New Yorker

1 / 1

1 / 1